Framing Statement

The Bricks Have Stayed the Same performed in the Great Central Warehouse Library (GCW) on the 5th May 2016, is an exploration of the site’s history as a grain depot, a builders’ warehouse and a university library. The piece is designed to direct the participants’ attention towards the ‘spaces’ and ‘non-spaces’ of the library, highlighting areas they may not have noticed before.

The Bricks Have Stayed the Same includes a series of, twenty minute one to one performances that are repeated throughout a duration of eight-hours (from 9am till 5pm).

The piece begins with a tour of the library which involves finding envelopes that contain information, – working similarly to a scavenger hunt. The aim being to draw attention to the site’s past.

The structure of the piece was inspired by Fiona Wilkies Mapping the Terrain (2002) and her notion that ‘the physicality of the site might offer ‘different stimuli elements’ to the creation process’ (Wilkies, 2002, 156), which related to our idea of highlighting various areas that illustrated GCWs’ history.

We aim to create an explorative pathway through the library, using these ‘different stimuli elements’. However, the instructions that guide the participants gives them the opportunity to explore the space, having learnt about the warehouse’s hidden features, without direct instruction or contact from the performers.

Participants are greeted at the library entrance, where they will receive their first clue from either myself or another performer. The intention is to lead the participants on a tour of the library, ending at the bottom of the staircase on the east side, overlooking the Brayford. In the ‘non-space’ underneath the stairs, there is an interaction with the participant, wherein they would be informed of the GCW’s history in greater depth.

The idea of drawing attention to ‘non-spaces’ has been prominent within our group’s initial ideas. Through our practice of ‘drifting’ inspired by Phil Smith’s Mythogeography: A Guide to Walking Sideways (2010), we identified the focus points that we want to emphasise in our scavenger hunt.

An integral part of the performance, would be a model of the library decorated with materials that represented the different uses of the space. Matching this, we aim to build an installation on the back wall of the space, displaying a timeline that illustrates the different functions of the warehouse.

During the performance, we would invite the participant to contribute to the timeline, using materials that are associated with the GCW’s history such as grain, charcoal and paper. This would happen whilst the participants are listening to information about the sites history and current features, from all three performers.

Using paper, we would create a basic frame for the timeline mapping the history of the GCW from its first existence up until the present day. The timeline would become enriched in real time by the participants during the performance slots.

Using the space under the stairs, whilst displaying the history through our installation elements, we would “take new forms of ownership of site, re-interpret the site, [and] keep its history and presence alive’” (Wilkies, 2002, 154). Therefore, using installation elements which the participant could contribute to, will provide them with opportunities to reflect on the knowledge learnt from the tour, and thus would ensure their attention is focused on the site’s history throughout the performance.

Analysis of Process

Exploring the space

At the beginning of the site-specific performance module, the group engaged in various exercises that aimed to help us focus on our surroundings. With guidance from our module tutor, we were encouraged to not think and just do because “if site specific performance involves an activity, an audience and a place, then creative opportunities reside in the multiple creative articulations of us, them, and there” (Pearson, 2010, 19). The Library is arguably a familiar building for most, if not all students. Therefore, trying to displace my preconceptions of the building to view it as a space rather than a place, was difficult from my perspective. One particular exercise that aided this, was ‘drifting’.

As a group, we would “allow the narrative of [our] walk to develop” (Smith, 2010, 19) and tour the library with no specific motivation. I noticed features of the Library that were never apparent to me before. It was during this first experience that our group were able to identify potential areas of the Library that we wanted to use for our piece.

Punchdrunk

Throughout our exploration of site-specific performance, we encountered a number of practitioners that helped to shape our final piece. Research into Punchdrunk Theatre Company aided the growth of our initial idea, as Punchdrunk are known for their immersive theatre experiences. The audience are encouraged to “explore rooms that have been transformed into performative spaces, ‘go with the flow’ or draw their personal mapping of the space and experience it at their own pace” (Papaioannou, 2010, 161). Punchdrunk ensure that their performances focus on the audience’s experience which is something we wanted to incorporate into our piece.

The initial idea – Scavenger Hunt

Taking inspiration from Punchdrunk, we proposed to create a scavenger hunt. Through research into Mike Pearson’s Site-Specific Performance (2010), we began to understand that “Site Specific Performance engages with site as symbol, site as story-teller [and] site as structure” (Pearson, 2010, 8). From this, we decided to focus on how the library is symbolic to students.

The idea was to find a poem in the library relating to the power of knowledge, as for students the library arguably symbolises knowledge. We wanted to take various words from the poem and scatter them throughout the library for the participant to find. Once all the words were found, the participant would be led by their final clue to a room with a glass window. The window would have had the poem written on it (minus the missing words that the participant had to find), leaving it up to them to re-order and write the missing words back into the poem.

We initially thought this idea had potential, however, we realised we were getting too caught up in the logistics of how to make the hunt complicated, rather than focusing on creating a performance which was specific to the history of the site itself. After this realisation, I believe we were able to focus on making the piece less complex and more site-specific.

Our proposal idea – Student Protest Tableau

Individual research conducted by Rebecca, discovered various national and international student protests that had occurred within the past decade.

The powerful and iconic images of these protests provoked our interest, as this linked to a previous student protest outside the Library in 2010. This sparked our second idea, to recreate the images of the student protests using our bodies. We realised that our previous idea (Scavenger Hunt) lacked the element of live performance, as it was more of an experience that the audience conducted themselves, with little involvement from us as performers.

However, one element of our performance that we wanted to keep prominent was the audience’s ability to interact with our tableau (if they chose to). For inspiration, we looked into Abramović and Ulay’s Imponderabilia (1977). Both artists stood naked in the entrance to a gallery where spectators would either ignore them and move between them or divert away.

We wished to recreate the audiences reaction of being both interested and possibly deterred by something unusual, as a result we too precaution choosing a location for our tableau. We came across the idea of transient spaces, which aided this idea; therefore, we looked for ‘non spaces’ in the library.

However, during our proposal, our module co-ordinator suggested that our initial ideas were arguably ‘site-generic’ rather than ‘site-specific’, as the student protests were not specific to the library itself. We found this feedback useful as it reminded us to focus on the specificity of the GCW in the creation of our performance.

Our third idea – Domesticating the space

Through the duration of the module, I realised that site-specific performance requires an appreciation for the site you are performing in. Rufford’s notion that “architecture articulates space, giving it a particular feel” (Rufford, 2015, 3) prompted us to revisit the space to revaluate its features. In order to gain new performance ideas, Rebecca and Molly ventured to the east staircase and sat on the stairs to engage with the space. Shortly after, they progressed to occupying the space underneath the staircase.

Our group spent a significant amount of time in the space, so that we could experiment with different techniques that would help us to interact with other students who were passing through and using the staircase.

Because we wanted to retain audience interaction in our piece, we discussed the possibility transforming the space to mimic a sleepover, to inject our own meaning into the space, by domesticating it.

For the benefit of the piece, we rehearsed the ideas generated so far, with the aim to create and discover interactions with the space, which could help make this idea more site-specific. We brought in cushions, blankets, fairy lights and portable lamps and wore pyjamas to immerse ourselves in the experience and transform the space.

We also had the idea of creating a small installation using books, to block the light from the windows, allowing the audience to in theory be further immersed into the intimacy of the comfortably made ‘non space’. However, despite the aesthetically pleasing installation of cushions and pillows, we were unsure how our book installation fit with our sleepover recreation, as although we brought the books in with the aim of creating some form of site-specific content, we ultimately agreed the ideas did not complement one-another.

Realisation – The Bricks Have Stayed the Same

Our final idea was developed by assembling all three ideas that we had created throughout the process, to create an amalgamation of all our work. We used my original idea of a scavenger hunt and adapted it so we could lead participants on a tour of the library whilst they searched for clues. These clues would reveal hidden features within the Library, that were related to the GCW’s history.

One piece of work we were particularly influenced by when developing our scavenger hunt idea was Forced Entertainments’ Dreams Winter (1994). This site-specific performance was inspired and designed for Manchester Central Library building. The piece was an T“attempt to test the space (its physical limits, its extraordinary acoustics, its ingrained still points [and] trajectories” (Etchells, 1999, 217).

Other practitioners that aided the development of the scavenger hunt was Punchdrunk. Similarly, to our piece, “Punchdrunk instructs its audiences – and not the performers” (Papaioannou, 2010, 161). This notion helped to assist the immersion experienced by the participants. Punchdrunk’s Against Captain’s Orders (2015) is also a site-specific performance which tours its audiences’ through familiar places, in order to help them to view the space differently to how they did before.

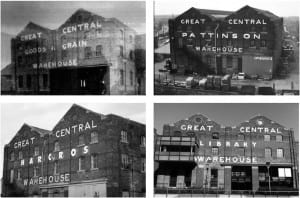

Rather than domesticating the space, an alternative suggestion made by Rebecca was to put paper along the back wall and create a timeline by sticking each of the four photographs of the GCW (see figure 1-4) onto the paper to show the transition of the building as it was used or was in disrepair. To maintain our desire of audience interaction, Molly suggested having audience members contribute to the timeline using various materials that would have been found in the warehouse during its different functions. These included grain, charcoal and book pages. We decided to accommodate an installation into our piece to support the historical facts and information we were going to enlighten our audience with as they were welcomed into the space.

Another idea I had that was integrated into our piece was having food to offer the participant once they were settled in the space. Rebecca assisted this idea by finding a recipe containing oats which is a type of grain, we then used other ingredients which weren’t necessarily kept in the warehouse, however, this represented the transition of the GCW from a grains and goods factory to a university library. By offering food, it also meant that we could ensure intimacy between the performers and the participant.

Our dialogue was projected in a casual and relaxed manner and consisted of the history of the GCW and explained the areas of the library that the participant had visited.

One of our most prominent influences Punchdrunk inclined our decision to provide gifts for our participants, similarly to the masks that were kept by the audience in The Drowned Man (2013). At the end of each performance, each participant would receive a small handmade box. This contained the materials that the participant would have used on the timeline (grain, charcoal, paper). They would also be able to keep their personal clock card and the clues they had to find on their scavenger hunt. By doing this, we wanted the audience to leave the space feeling enlightened, reminding them of their newfound knowledge of the history of the GCW, in an attempt to help the participants, appreciate the building they thought they knew.

Performance Evaluation

Having performed The Bricks Have Stayed the Same, there were numerous strengths and weaknesses that were identified during the performance. The initial scavenger, hunt was completed with few interventions. However, there were occasions where participants were unsure of where they had to go in order to find the next clue. This meant I (as the ‘timekeeper’) had to intercept and direct the participant in the correct direction of the next clue, in order to ensure that the participant finished the hunt within a certain duration.

This was not ideal as our aim was to allow the participant to navigate their own path, however, with the time constraints we had in place this was not possible. If we were to perform this again, we would ensure that we expanded our time constraints so that participants can go about their journey without being interrupted. The performance was an invite-only audience which meant that only 12 people got to experience it. The nature of the piece meant that it would have been difficult to allow uninvited audience members to experience the performance, as we would not be able to purchase an extensive number of materials in the event that more people wanted to participate.

If I were to repeat the piece, I would expand the group of performers, as although we worked effectively as a team (a quality that I would not wish to change) a larger group could allow us to take shifts and extend the length of our piece to allow more participants to take part. Our location under the stairs helped us to create an intimate and immersive environment, which allowed the participant to focus on the history of the site in a one on one, exclusive experience.

Another positive aspect of our performance was the select three participant’s willingness to wear my GoPro Camera, which recorded our performance and allowed us to reflect back on it afterwards. In order to get a wider range of material, if we were to perform the piece again I would also ensure that everyone wore my GoPro Camera so we could get a full account of everyone’s journey through the space. However, I have considered the possibility that the participants may have been more invested in wearing the GoPro and recording good quality footage for us rather than allowing themselves to be immersed in the performance.

Figure 16. Perfomance Footage (Sophie Tahssein, 2016).

Ultimately being able to experience the site-specific performance module has altered my perception of the actor-audience relationship. I was particularly interested in the actor and audience sharing the same space, which allowed me to think of new ways to interact with audience members. Working in a non-traditional performance space, and being encouraged to work by doing and not necessarily thinking, initially presented challenges to my devising process. However, the overall process allowed me to discover a new way of thinking, recognising empty ‘spaces’ and ‘non spaces’ as possible undesignated stages to create performances in.

Word Count: 2657

Bibliography:

Abramović, M. (1977) Imponderabilia. [Performance Art] Bologna, Italy: Galleria Communale d’Arte Moderna.

Etchells, T. (1999) Certain Fragments. London: Routledge.

Forced Entertainment (2016) About. Available from http://www.forcedentertainment.com/about/ [accessed 8 May 2016].

Forced Entertainment. (1994) Dreams Winter. [Performance] Tim Etchells (dir.) Manchester: Manchester Central Library, 15 July.

Hall, M. (2016) South Africa’s student protests have lessons for all universities. Cape Town: The Guardian. Available from http://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2016/mar/03/south-africas-student-protests-have-lessons-for-all-universities [Accessed 12 March 2016].

Norton, C. (2010) Lincoln students taking to the streets again against education cuts. Lincoln: The Linc. Available from http://thelinc.co.uk/2010/12/lincoln-students-taking-to-streets-again-against-education-cuts/ [Accessed 12 March 2016].

Papaioannou, S. (2014) “Immersion, ‘Smooth’ Spaces And Critical Voyeurism In The Work Of Punchdrunk”. Studies in Theatre and Performance, 34(2)160-174. Available from http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=b995b4ef-84f2-48a0-affe-99aade1478b3%40sessionmgr106&hid=112&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#db=ibh&AN=97901837 [Accessed 8 May 2016].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Punchdrunk. (2013) The Drowned Man. [Performance] Felix Barrett and Maxine Doyle (dir.) London: Temple Studios 31 London Street.

Punchdrunk. (2015) Against Captain’s Orders. [Performance] Peter Higgin (dir.) London: National Maritime Museum.

Rufford, J. (2015) Theatre & Architecture. Palgrave Macmillian.

Smith, P. (2010) Mythogeography: A Guide to Walking Sideways. Devon: Triarchy Press.

Sophie Tahssein (2016) The Bricks Have Stayed the Same [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXCYkCoAP7Y [Accessed 12 May 2016].

Wilkies, F. (2002) Mapping the Terrain: A Survey of Site-Specific Performance in Britain. New Theatre Quarterly, 18(2)140-160. Available from https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/pid-1226692-dt-content-rid-2260297_2/courses/DRA2035M-1516/DRA2035M-1415_ImportedContent_20141103010200%281%29/wilkie-mapping-the-terrain%20.pdf [Accessed 8 May 2016].