Framing Statement: What is site specific performance?

Site specific performance is hard to define as it is fluid and ever changing. One definition of it is how “layers of the site are revealed through reference to: historical documentations, site usage (past and present)” (Wilkie, 2002, 150). This informed our initial research processes and framed our final performance. Nick Kaye explains that site “define[‘s] itself through properties, qualities or meaning produced in specific relationships between and ‘object’ or ‘event’ and a position it occupies” (2000, 1). Here Kaye makes reference to the relationship between a site and the performance taking place in the site and how exploring the site creates meaning; from that meaning creates performance.

Our Performance

Our performance consisted of a scavenger hunt throughout the library to highlight parts of its previous self. It ended under the east staircase where we created a timeline of the library from 1907 to 2016 (see below).

The history of a site can be a “vehicle for remembering,” and its location acts as a “mnemonic trigger, helping to evoke specific past times related to the place and time of performance and facilitat[es] a negotiation between the meaning of those times” (Harvie, 2005, 44). Our piece was designed to fulfil these aims by creating a timeline of the library.

We aimed to inject meaning into the space as this is the most recent extension of the library and lacks the historical significance of the main building. The invited audience/participants were integral to the performance, we focused on them and their input. The performance spanned an 8-hour period. We gave every participant a 20-minute slot to engage with the performance: during the first 10-minutes they would take part in a scavenger hunt around the library. This would lead to our site (fig.3), where they would interact with the space and the performers for the remainder of their time.

Our piece was influenced predominately by the theory of Fiona Wilkie and Mike Pearson’s Site Specific Performance. Practically by Forced Entertainment’s Nights in This City and Dreams’ Winter, Marina Abramovic’s Nightsea Crossing, Rhythm 0 and Seven Easy Pieces, and finally the works of Punchdrunk.

An Analysis of Process

Scavenger Hunt

When reading Mapping the Terrain I began to understand that site “enable[s] [its] audience to have a ‘radically different relationship’ to the performance” (Wilkie, 2002, 154). Drawing from this our group realised we wanted the audience to be the main focal point, as we wanted our site performance to “not just about a place, but the people who normally inhabit and use that space. For it wouldn’t exist without them” (Wilkie, 2002, 145). Sophie suggested the idea of a scavenger hunt through the library, which led to focusing on knowledge and its place within the library. We would split the participants into two groups, giving them verbal instructions. They would need to find books that had historical or cultural importance, and held a word inside they would need for later. They would move to the ground floor with a collection of words that would be used to fit into a predetermined poem which would be left as an installation.

This idea was too convoluted, because of the excessive focus on books and rules; we felt that perhaps the audience were doing too much and we were not doing enough. Couillard’s reflections on site-specific claims that “the location [is] integral to the overall form and content of [the] performance, making it impossible to separate the “location” from the “work” (2006, 32). From this, our initial idea was too generic and could not work as site-specific. It focused too much on fiction and not fact, and therefore we wanted to explore the historical meaning of this building and its place in the community.

Student Protests

From our initial idea we attempted to find something we were passionate about which could involve the use of space and live performance. The audience were still important but would not become a predominant part in the piece. We wanted to explore our input and presence in the piece, which led me to think about the importance of the student body and our place in the community. I researched student protests as, in recent years, students have been protesting globally, focusing on rising student fees. I felt passionate about this project as I thought it would be interesting to do a political site-specific piece.

We identified the lifts and the bottom of the stairs as an appropriate site as we realised they were places of traffic. This meant that people would have the option to stop and look, pass through us or simply ignore us. Marina Abramovic’s Imponderabilia informed this idea as “the crucial factor was that everybody had to decide whom to look at as they passed” (Haberer, undated).

We researched local and international student protests and decided to recreate the images from a selected few of these protests through tableaux.

When developing this idea, I studied Abramovic’s Seven Easy Pieces. She recreated iconic art work with her body, which led me to be interested in her “reperformances of each of these works involved extended acts of posing in the positions captured in these images.” (Shalson, 2013, 437). This influenced our tableaux as we decided that they should change every hour for 8-hours. Additionally, we would hold signs with the name of the protest so people knew what we were representing.

Despite the passion we had for this idea we realised that we were moving away from site specificity and into site generic. We realised that we needed to alter this idea into something we could feel equal passion for.

Domesticating the Space

At this stage we attempted to find an overlooked space in the library. Molly and I sat on the east stairs for a few hours and generated no ideas, so we decided to explore the space beneath them. We sat under there for hours waving at people and talking to passers-by. We gained a lot of attention which led us to spend more time investigating the space.

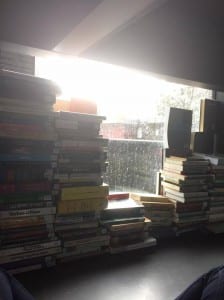

Pearson suggests “site may facilitate the creation of a kind of purposeful paradox […] through the employment of orders or material seemingly unusual, inappropriate or perverse at this site” (2010, 36). This sparked the idea to bring a mattress under the stairs to create intimacy. We thought about domesticating the space, using books to cover the windows in order to create a micro-world within this small space (fig. 6 and 7).

After filling the windows with books we questioned how this was site specific. During our process we had two audience members in the space, and to try to make it site specific we retrieved books from the library and began to read aloud. We gave them paper and asked them to create something based on what was spoken. The performance was ephemeral so each of the participants would have completely different experiences. This was inspired by Forced Entertainment’s Dreams Winter. Tim Etchells said they “were drawn to the idea of animating the stories and secrets contained in all the books, […] and the ghosts of past library users” (Cranitch, 1994). Our idea was less about telling stories, but more about invoking something in the participants, enabling them to contribute something to the space.

Although we liked this idea we struggled to make it site specific. Once in the space we felt it would work better as an installation. It seemed as if we were looking more at “site as symbol” (Wilkie, 2002, 158). Despite this we decided to remain in the space because of the intimacy that it provoked.

Final Idea – The Bricks Have Stayed the Same

Upon reflection of our previous ideas, we decided to adapt the best parts of each idea and merge them together to create a performance. We kept the concept of the scavenger hunt and the factual nature of the student protest because it resonated with the site. Despite this we still wanted to create our performance under the stairs.

To make the idea more site-specific I suggested we should place white paper on the back wall with pictures of the library. Molly suggested we bring in materials that have previously been housed in the warehouse such as grain, coal and paper, to use as tools so the participants could contribute to the wall. Abramovic’s Rhythm 0 shaped this idea as she too placed tools in a space and let her participants use them as they saw fit on her body.

We focused on researching the library as it “is imbued with history” (Shantz, 1998, 337), and created a timeline of the library with important historical dates:

The research into the history of GCW became our dialogue as we attempted to “engender ideas of place and community” (Wilkie, 2002, 144), through a dialogue with the audience. Furthermore, we realised the site we selected had never been inhabited before: it had been a transient space without meaning. We wished to bring people into the space and allow them to “experience the environment from a new perspective” (Govan et al, 2007, 120). This would be achieved through the transformation of an empty, unused space into a domesticated area in which participants were free to be creative, whilst also learning something new.

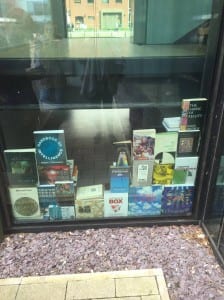

I thought we should create a miniature version of the library and decorate it with photos of the companies that have previously owned it, creating a collage. The back wall would show a clear timeline of the library’s life yet the scaled down library (see fig.8) would show all of the history tied together. This would give historical depth to our performance, not just through transformation of the space but through sculpture.

When revisiting the scavenger hunt idea, I looked at Forced Entertainment’s Nights in this City. It is described as “poetical and mischievous […] historical” (Forced Entertainment, 2016). After researching this I thought of using QR codes to direct the audience around the library. However, there was a technological issue with this as participants would need a smart phone with the app on to take part. Instead we wrote riddle-like dialogue inspired by Tim Etchells, as it felt more personal to write it because we wanted to focus on connecting with the people in the library.

By experimenting in the space we encountered some practical issues, as people were moving the envelopes around and some people did not fully understand the clues. It became apparent that we needed to re-write the clues but with more instructions. We put the clues into envelopes and fixed them to parts of the library. Sophie suggested we have food in the performance so I found a recipe for oat energy bites and we made them. Although the oats established a link to the library’s grain warehouse past, the food represented a mixture of the old and the new which is how the library itself was constructed.

The final piece was interactive and heavily engaged the audience. Our final thoughts for the piece were to greet the audience as they entered, and have a time-keeper secretly track them until they reached the site where they met all of the performers. We got this idea from Punchdrunk as they introduce the actors throughout their performances then meet them at the end. I also thought we should give the audience something at the end to take away so we made boxes which contained materials that the library held in its history. This was also inspired by Punchdrunk as they let people keep their masks at the end of The Drowned Man.

Performance Evaluation

On reflection I feel the one-on-one intimate nature of the piece worked well, as if we had invited more than one person in the space at a time it may have become cramped. We had a member of the public ask us what we were doing so our secondary audience engaged with the performance, which I was not expecting. The audience involvement was varied. We asked people to contribute to the timeline and the model of the building. Instead of telling people to draw something we gave them free reign (see fig.9 and 10). Looking back on this I feel specific guidance may have engaged the audience more creatively.

There were things that worked well in the performance such as the intimate nature of the piece. By creating our performance in a small space we were able to effectively initiate one-on-one dialogues with our audience, which would not have been as effective within a larger, more open space. The way we orchestrated the narrative made sure that no two people had the same experience; it was ephemeral and personal which enabled the performance to be unique to each participant (see video below).

Credit to: Kieran Spiers, Rob Anthony and Holly Marshall for filming (2016)

Sophie Tahssein for editing (2016)

The scavenger hunt allowed people to see the library in a different way and got them to interact with the space in ways they would not necessarily have done previously. A member of our audience said “I very much enjoyed the one-on-one section under the stairs” (Rowan, 2016). Another said “I felt like you took me through a journey of [GCW’s] life and I found things out I never would have known without participating in your performance” (Brunt, 2016). This shows engagement with the performance and an appreciation of the history of GCW.

Despite our successes there were things we could have improved on, especially the attention to detail. The library staff instructed us to protect the floor, so we used plastic sheeting. However, we could have used material like hessian as it looks like grain bags and therefore more specific to the site. The seeds could have been in pots instead of in the bags, which would have been interesting as seeds grow out of pots and in relation to the site, ideas grow out of a library. The model of the building could have been used in a more interactive way to facilitate our information about the library.

We thought a factual account of GCW would have been useful whilst still injecting fun into the space using the timeline creatively. However, upon reflection if we had woven the experience into a story it could have been more engaging for participants. The placement of the clues could have been improved, we had difficulty finding a place for the second clue near the winch. If I had the chance to do this performance again I would spend more time experimenting in the space with different methods.

The final performance triggered new ideas. Whilst in the space waiting for participants I listened to the world around me and noticed little details about the space that gave it its character. From this I thought we could have created an installation piece using the sounds in the space. I would have had instructions on the audio asking people to look at certain things such as the area outside and then explore the space in more detail.

Whilst I understood the theory of site and its place in the performance art sector, I found it difficult to apply the theory practically, which created friction between myself and the module. I struggled to separate how I view the library as a study space and viewing it as potential performance place. This made it hard to concentrate during the module and generate ideas. I feel this impinged upon our performance as during the piece, when there were no participants as a group we found it difficult to view it as a performance space. We could have conducted ourselves in a more professional manner. If we did the performance again I would try to rectify all of these issues and have more fun with the piece.

Word Count: 2747

Works Cited:

Abramovic, M. (1977) Imponderabilia. [Performance Art] Bologna, Italy: Galleria Communale d’Arte Moderna.

Abramovic, M. (1974) Rhythm 0. [Performance Art] Naples, Italy: Studio Morra.

Abramovic, M. (2005) Seven Easy Pieces. [Performance Art] New York, USA: Guggenheim Museum, 9 November.

Brunt, E. (2016) Questions on our Site-Specific Performance. [interview] Interviewed by Rebecca Fallon and Molly Richards Siddall, 11 May.

Couillard, P. (2006) Site Responsive. Canadian Theatre Review. (126) 32 – 37.

Cranitch, E. (1994) Quiet please, mayhem in progress: From off the wall to off the shelf: Forced Entertainment’s latest theatre piece takes a leaf out of the Manchester Central Library. Ellen Cranitch reports. [online] Independent. Available from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-quiet-please-mayhem-in-progress-from-off-the-wall-to-off-the-shelf-forced-entertainments-1413545.html [Accessed 7 March 2016].

Dubin, J. (2015) Why South African Students Are Shutting Down Universities – The country’s president bows to students’ demands and freezes fee hikes. [online] Vocativ. Available from: http://www.vocativ.com/242477/why-south-african-students-are-shutting-down-universities/ [Accessed 10 March 2016].

Forced Entertainment (1994) Dreams’ Winter. [Performance Art] Manchester, UK: Manchester Central Library

Forced Entertainment (1995) Nights in this City. [Performance Art] Sheffield, UK: Moving bus.

Forced Entertainment (2016) Nights in this City. [online] Forced Entertainment. Available from http://www.forcedentertainment.com/project/nights-in-this-city/ [Accessed February 29 2016].

Govan, E., Nicholson, H. and Normington, K. (2007) Making a Performance Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices. Oxon: Routledge.

Haberer, L. (undated) Imponderabilia 1977. [online] New Media Encylopedia. Avaliable from: http://www.newmedia-art.org/cgi-bin/show-oeu.asp?ID=ML002604&lg=GBR [Accessed 25 March 2016].

Harvie, J. (2005) Staging the UK. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Kaye, N. (2000) Site Specific Art Performance Place and Documentation. Oxon: Routledge.

Norton, C. (2010) Lincoln students taking to streets again against education cuts. [online] The Linc. Avaliable From: http://thelinc.co.uk/2010/12/lincoln-students-taking-to-streets-again-against-education-cuts/ [Accessed 10 March 2016].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Punchdrunk. (2013) The Drowned Man. [Performance] Felix Barrett and Maxine Doyle (dir.) London: Temple Studios 31 London Street.

Rowan, B. (2016) Questions on our Site-Specific Performance. [interview] Interviewed by Rebecca Fallon and Molly Richards Siddall, 11 May.

Shalson, L. (2013) Enduring Documents: Re-Documentation in Marina Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces. Contemporary Theatre Review. 23 (3) 432 – 441.

Shantz, C. (eds.) (1998) Dictionary of the Theatre Terms, Concepts and Analysis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Wilkie, F. (2002) Mapping the Terrain: A Survey of Site-Specific Performance in Britain. New Theatre Quarterly. 18 (2) 140 – 161.